【竹山研究室】Takeyama Studio 2015 : Chorus

建築を設計する行為はつねに他者とのかかわりを持つことである。

設計者は想像した空間と、その空間を置き換えたもの(言葉やダイアグラムなど)との間を絶えず行き来しながら建築を構想する。

また、ものとしての建築はそれを取り巻く様々な物理的条件の中でしか存在し得ない。光、風、雨といった自然現象だけではなく、風景や匂い、響き渡る音まで、あらゆる場所の力を受け止め、それに応答しながら固有の場を生み出す。

他者との関係は多義的であり、多様な他者との関係を把握する手がかりとして、私たちはまずChorus/Choraが言及された文献の輪読と議論を重ね、さまざまな角度からその概念を理解することからプロジェクトをはじめた。

■Studio Diary

Reading:

Chorusの概念は多義的で隠喩的であり、幾度も意味の派生を経て演劇・音楽の専門用語にもなった。

まず私たちはその意味を限定するのではなく、重畳された多義性をそのまま受け止めるために、“Chora”

の概念を手がかりとした。私たちが講読した文献は三冊。まずChoraの概念の初出ともいえるプラトンの

『Timaeus』から始まり、メディア学者であり、デジタル時代における文書の書き方(Hyper-text)について論

ずるG. Ulmerの『Heuretics: The Logic of Invention』、そしてピーター=アイゼンマンとジャック=デリダが

ラ・ヴィレット公園の設計に関わるプロセスをまとめた『Chora L Works』の順に読み進めた。

150409 Project Brief

Chorus

古代ギリシアのコロスχορός, khorósに由来する。

円形野外劇場の中心に位置を占め、ギリシア悲劇の進行を司るコーラス。

多数の声の重ね合わせを通して、場を生み出し、その場に集まる人々の身体を包み込む世界をつくり出す。

鳥もまた歌いながら自らのテリトリーを主張する。

原初的な場を主張する表現としてのChorus

竹山聖

150414

Reading:

Heuretics: The Logic of Invention

Gregory L. Ulmer

Heuretics: The Logic of Invention

The Johns Hopkins University Press

1994

That is how I am going to invent chorography──by creating the field within which the insight I seek already exists. Compose a “diegesis”──an imaginary space and time, as in a setting for a film──that functions as the “places of invention,” using this phrase in the sense associated with it in the history of thetoric. ……

In order for rhetoric to become elctronic, the term and concept of topic or topos must be replaced by chora (the notion of “place” found in Plato’s Timaeus).

…… Here is a principle of chorography: do not choose between the different meaning of key terms, but compose by using all the meanings (write the paradigm).

Chora, then, evokes together the thought of a different kind of writing (without representation) and adifferent mode of value. The participants agree that the seeming impossibility of “representing” chora could make their project exemplary: the goal is not just to design a folly but to explore the invention process itself by means of this problem: ……

…… The impossibility of chorography is analogous to Eisenman’s difficulty when he accepted chora as the program for his folly. He had to give architectural form to that which is unrepresentable. My problem, in inventing an electonic rhetoric by replacing topos with chora in the practice of invention, is to devise a “discourse on method” for that which, similarly, is the other of method.

150421

Reading:Timaeus

プラトン 種山恭子・田之頭安彦訳

プラトン全集12 ティマイオス

岩波書店

1975

まず一つには、同一を保っている形相というものがあるのですが、これは、生じることも滅びることもなく、自分自身のなかへよそから他のものを受け入れることもなければ、自分のほうがどこか他のものの中へ入って行くこともなく、見えもしなければ、その他一般に感覚されることもないものなのでして、じっさいこれは、理性の働きがその考察の対象として担当していることろのものなのです。そして、以上のものとの同じ名で呼ばれ、また以上のものににているものが、二つ目です。これは、感覚され、生み出され、いつでも動いており、ある場所に生じては、再びそこから滅び去って行くものなのでして、思わくによって、感覚の助けを借りて捉えられるものなのです。そして、さらにまた三つ目に、いつも存在している「場」の種族があります。これは滅亡を受け入れることなく、およそ生成する限りそのすべてのものにその座を提供し、しかし自分自身は、一種の擬いの推理とでもいうようなものによって、感覚には頼らずに捉えられるものなのでして、ほとんど所信の対象にもならないものなのです。そして、この最後のものこそ、われわれがこれに注目する時、われわれをして、「およそあるものはすべて、どこか一定の場所に、一定の空間を占めてあるのでなければならない、地にもなければ、天のどこかにもないようなものは所詮何もないのでなければならない」などと、寝とぼけて主張させる、まさに当のものにほかなりません。

150428

Reading:CHORA L WORKS

Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman /

Edited by Jeffrey Kipnis

and Thomas Leeser

CHORA L WORKS

The Monacelli Press

1997

JD Of course, chora cannot be represented in any form, in any architecture. That is why it should not give place to an architecture ― that is why it is interesting. What is interesting is that the non-representable space could give the receiver, the visitor, the possibility of thinking about architecture. PE

Yes, that’s it! That’s it, that’s it, that’s it. JD While chora is impossible to represent, we can train. . . . PE

That is the beginning. How to think about the impossibility of representing this being. JD Of representing, for instance, an architecture of representation, of chora. PE Exactly. JD So, it’s impossible. That’s the limit, that’s the boundary. You have to draw a limit. It would be a solid limit, which could represent, so to speak, the limit that the receiver, the visitor, the reader would reach. PE Yes. But the more we begin to take these things into account, the more we assume materiality. We can’t just talk to them on the site. We have to efface all the forms we make, decontaminate traditional representation. No matter how much we say, “this is chora”, we don’t want the visitors to feel “no, it’s not, it’s a table.” We will have to erase and efface to get to chora. The way we get there is chora. JD And at the same time,

you have to keep something; you cannot erase everything. You have to keep . . . PE The mark of the erasure. JD Yes. It’s the form of the limit that is to be decided. PE Yes. If you take the whole of the table away, then you have nothing. What we have to do now is to write the program for the training of the readers ― to find a means of de-programming them from their traditional reading of architectural representation and of introducing them to the possibility of the discursive, rather than the figurative, in architecture. Nevertheless, we have to figure our discourse. Now for the question of the limits. What

is the limit of moving from the discourse, in and about your text, to figuration? What can be made figurative? Hence the need of a figure for your text.

Discussion:

論議は、一般的で抽象的な概念から、特殊で具体的な思考へ、哲学的概念から建築での応用へ向かって進んでいった。その過程はChorus/Choraの異なる意味を分類し限定するより、あらゆる意味の重ね合わせとして把握することであった。

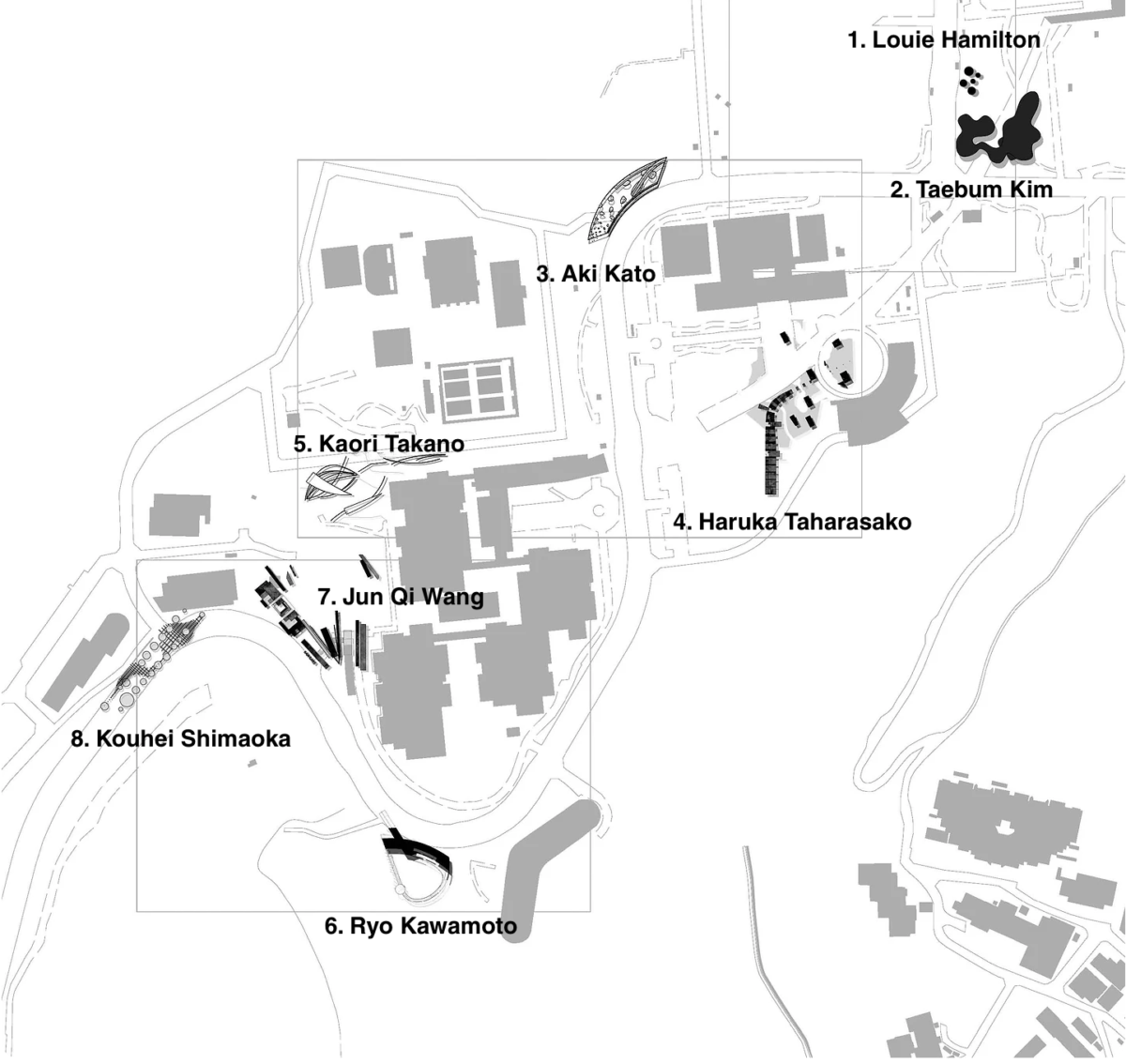

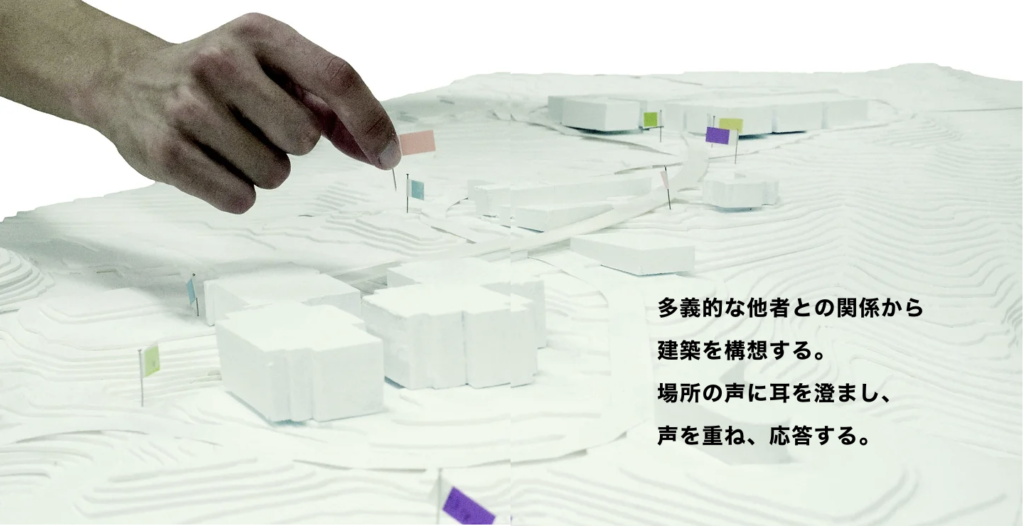

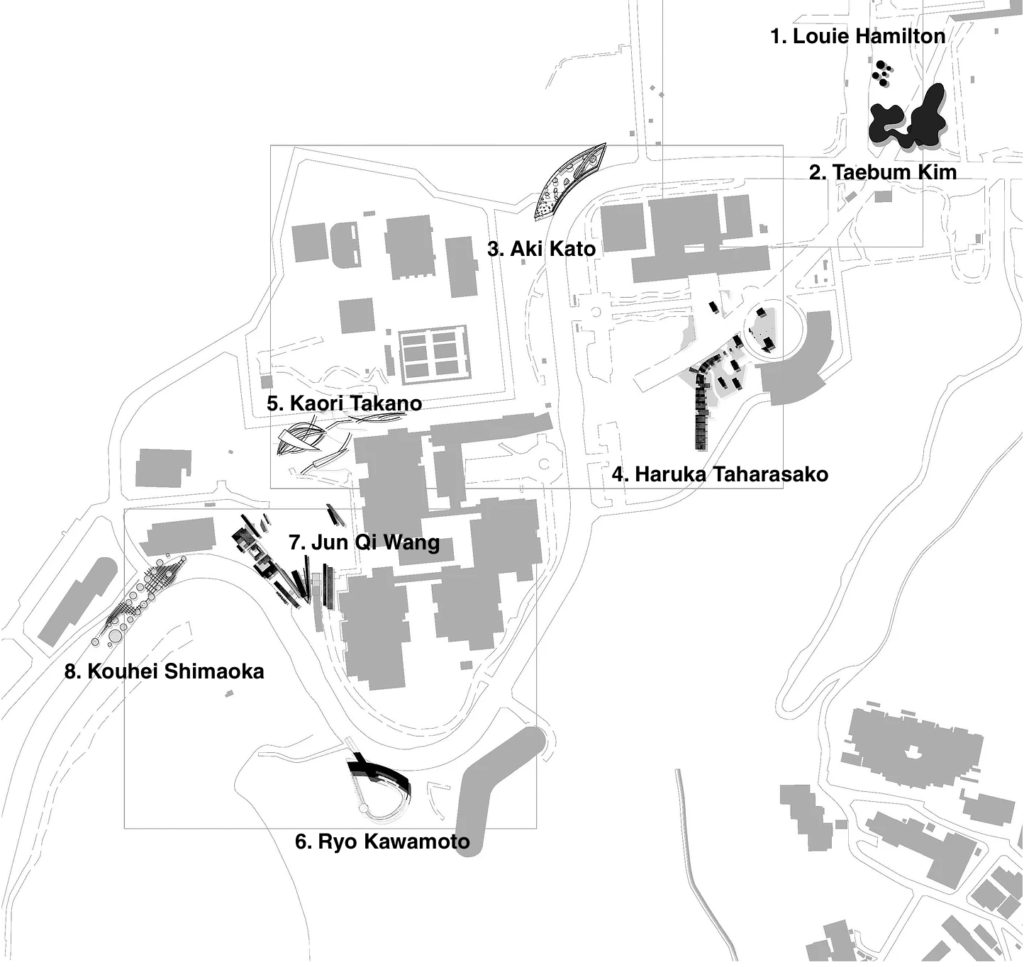

■Studio Project

京都大学桂キャンパスの中で各自の敷地をプロットし、その場所の持っている音に、他者の声に耳を澄ませ、応答する建築を構想する。耳を澄ませることは、文字通りに物理的な「音を聴く」ことでも、メタファーとして「何かを受け止める」ことでも解釈することができる。風の動きを、風景を、森の音を、太陽の動きを受け止め、応答する。さらには、コーラスとコーラの語源が同じであることから、他者の声に耳を傾けながら自身の声を重ねていき全体を構成した。

1. Louie Hamilton

2. Taebum Kim

3. Aki Kato

4. Haruka Taharasako

5. Kaori Takano

6. Ryo Kawamoto

7. Jun Qi Wang

8. Kouhei Shimaoka