【ダニエル研究室】Paris Tea Pavilion

Kyoto University

Thomas Daniell

Challenge

The pandemic panic that began in early 2020 triggered many new rules and codes of behavior, which temporarily transformed various aspects of daily life, notably in education. At Kyoto University, face-to-face teaching became very difficult, or impossible. Students were forced to stay home, and in some cases foreign students were not able to enter Japan. Consequently, most classes took place online, with students watching live lectures and submitting assignments according to programmed deadlines (taking into account time-zone adjustments).

These changes obviously had a negative effect on the usual teacher-student interactions and discussions, as well as relationships between students inside and outside the classroom. The formative experiences of university life – a process of socialization and maturation, of making friends and connections, of learning to participate in the intellectual discourse of seminars and laboratories – was replaced by an enforced isolation that led to psychological and motivational problems among students and teachers alike. Students all too easily stopped paying attention to their screens, and teachers found it difficult to spark responses from them. Yet, as online teaching became more accepted and normal, the limitations being imposed also opened other opportunities. If it were indeed possible to teach effectively without regard to physical proximity or temporal alignment, then what else might be possible? Holding classes online means that students did not need to be in the same room, the same city, or even the same country, and this also allows students anywhere to communicate and collaborate in virtual environments, in real time.

Response

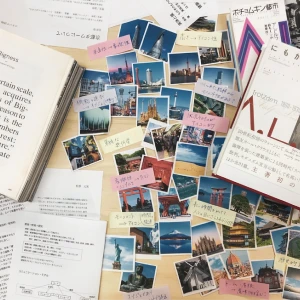

In the first semester of 2021, Daniell Lab initiated an international joint design studio, using a combination of online and face-to-face teaching. Supported by ADAN (Architectural Design Association of Nippon, led by architects Shuhei Endo and Kiyoshi Sey Takeyama), this was a collaboration with students at ESA (École Special d’Architecture) in Paris, France, led by Professor Frank Salama, and students at Osaka Sangyo University, led by Professor Noriyuki Hikida, and one student from Osaka Institute of Technology, led by Professor Asako Yamamoto. The visiting critics were Kentaro Takeguchi, a partner in the Kyoto-based architecture office Alphaville, and structural engineer Ryo Watada.

The assigned task was to design a pavilion for a site on the bank of the Seine River, adjacent to Asile Flottant, a boat designed by Le Corbusier in the early twentieth century. The ultimate goal was for the students to go to Paris at the end of the semester, and actually build the pavilion.

All sessions took place over Zoom, using large monitors installed in each studio. The students of each school would gather in their respective studios, or participate from their homes. Classes were scheduled during evenings in Japan and mornings in France, allowing a global simultaneity with live communication. Outside regular class hours, the students shared their design ideas and presentation files using private video communication and online group chats. The negative consequences of online teaching were thereby turned into a stimulating and inspiring opportunity, creating new relationships rather than damaging existing ones.